History and Purpose.

If you’ve been involved in education circles for any amount of time you’ve probably heard something about Title I funding. Title I funds have been a very important component of school budgets for almost 60 years. Title I is the largest federal entitlement grant for New York City public schools. Originally enacted as part of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) in 1965, Title I was reauthorized under both the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) act and Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) and is generally reauthorized every five years. The purpose of Title I as per the original ESEA is to “provide all children significant opportunity to receive a fair, equitable, and high-quality education, and to close educational achievement gaps.” The original intent for Title I funding was to provide additional financial assistance to school districts serving low-income children facing challenges that might not be found in wealthier school districts. Currently, the law mandates Title I assistance to ensure that all children meet challenging state academic standards.

Title I for NYC Public Schools.

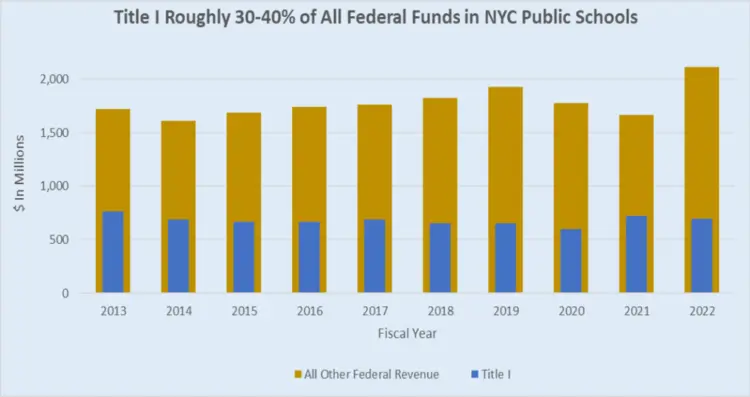

NYC public schools have received an average of $680 million annually in Title I over the last decade although funding has dropped 9% in the last 10 years. In the same time period, Title I money has represented an average of 38% of all NYC public schools’ federal grants not inclusive of special federal assistance such as American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA), American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA), Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Act (CRRSA), and Coronavirus Aid Relief and Economic Security (CARES) funds. The next largest federal allocations (which are both much smaller in the $300 million dollar range) are for school lunch and Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) programs for the disabled.

Eligibility.

Title I allocations are based on the count of numbers of children who are eligible. As stated before, Title I is an entitlement grant which means funding is determined by formula and eligibility is based on certain criteria. If you meet eligibility standards you are “entitled” to receive the allocation. A child is “eligible” if they are ages 5 to 17 and living in a family with income below the national poverty level or receiving Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) or are considered a neglected and delinquent child in a locally funded institution or are a foster child.

Census, Poverty Counts, and Per Capita.

Census data plays a key role in determining the amount of Title I money that any school district can receive because the count of children in poverty is estimated through the Small Area Income and Poverty Estimates (SAIPE) program of the U.S. Census Bureau. NYC schools are subject to something called the County Provision. The County Provision requires the Title I funds allocated to New York City from the Federal government, be further allocated among the five boroughs in proportion to each county’s share of poverty counts. For example, this means schools in the Bronx will get a per child allocation based on the share of poor students in the Bronx. Here’s what the per child allocations look like by borough in the current 2022-2023 school year, in order from largest to smallest.

The other factor affecting school allocations is the comparison of a school’s poverty count to its county poverty cutoff rate. This determines if the school is eligible to be a Title I school. If a school’s share of low-income students relative to its total enrollment (the school’s poverty rate) is equal to or exceeds its county’s poverty cutoff rate, it can be Title I eligible. Here are the current county poverty cutoff rates in the current 2022-2023 school year, in order from largest to smallest.

One nice feature of Title I is that schools can become school-wide programs. This contrasts with schools with small numbers of eligible students (below the county poverty cut-off rate) who still qualify for Title I “Targeted Assistance”. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, across the Country 95 percent of children served by Title I receive services in schoolwide programs that serve all children in the school, regardless of whether they are formula eligible or not. Altogether, about 11.6 million children are counted as formula eligible in the United States, but more than twice that amount (about 25 million students) receives Title I services.

Recently Chalkbeat wrote that some NYC schools are exploiting a loophole regarding their qualifying percentages of low-income students. I can’t speak to the efficacy of verification systems within the central administration of NYC public schools but if the claims are true, city schools could be open to federal reprisal and would be well advised to seek proper adjustments to the poverty cutoff rates and undertake citywide re-assessment of school eligibility to accurately reflect numbers of Title I eligible students. Title I funding has been too critical of a resource to risk loss of funding.

Uses of Title I.

A well-known key feature of Title I is that it must be used only to supplement funds that are already in use and never to supplant or be used instead of funding that’s already being used. Title I funding is allowed to be used for academic intervention, credit recovery, counseling, and school based mental health (but without reducing budgets that public schools are already using on these activities). Title I is also allowed to be used for support staff supporting Title I programs such as non-instructional Teacher Aides and Title I Coordinators. Program supplies and materials are allowable purchases along with activities for parent and family engagement. Professional development that is aligned with Title I is also an approved activity along with a limited list of other activities such as field trips with academic content, post-secondary education prep including things such as advanced placement classes that count towards college credit, and nominal, non-monetary student awards for effort and achievement.

Some Misunderstandings About Title I.

One common misunderstanding is that Title I is only for English Language Arts and Math but, schools that have become school-wide programs can use funds to support all academic areas that need improvement not just English Language Arts or Math. The same is true for schools that only receive targeted assistance, but it is slightly more difficult because funds must only be used to support eligible Title I students. Another misperception is that Title I can only be used for remedial activities, but it can also be used for accelerated studies as well. Title I may also be used for non-instructional activities and strategies designed to raise the achievement of low-achieving students such as attendance improvement, mentoring, and bullying prevention activities. One other misperception is that although Title I eligibility leans on counts of school children between 5 and 17 years old, regulatory guidance describes Title I funds can be used in a preschool program to improve cognitive, health, and social-emotional outcomes for children from birth to school age, which is the kindergarten level in NYC. Preschool programs are considered as designed to prepare children for success later in school and therefore meet the general spirit and intent of Title I.

Photo by Reynaldo #brigworkz Brigantty

Remaining Questions About Title I.

In the past I have gotten specific questions about schools that have lost Title I funding. I always interpret this to mean that a school had previously gotten Title I but for some reason that hasn’t been shared, is no longer eligible to receive the funding. The school leadership along with public school central administration should unpack the reasons in each specific case but here are the possibilities. One, the county poverty cutoff rate has changed and although the school has the same share of low-income students, the school’s poverty rate is lower than the applicable county rate. Two, the county poverty cutoff rate has not changed but there are fewer low-income students enrolled at the school which has the same result of lowering the school poverty rate below the applicable county rate. County poverty rates are slow to change especially because they are indexed to census data but over time they can change. Below is a table showing rates in 2013 as compared to rates in 2022.

In case you’re wondering how schools with suddenly low poverty rates can continue to be Title I funded, grandfathering allows schools that are no longer Title I eligible to retain their Title I status for one additional year. At the start of this school year according to the Title I school allocation memo, 8 NYC public schools had grandfather status. Each of the schools had poverty rates that were lower than their respective county poverty rates. The schools had an aggregate projected enrollment of more than 4,400 students who (if enrollment remains stable for next year) could be affected if the schools cannot maintain Title I eligibility. Each school happens to be a Title I school-wide programs school. Loss of Title I for these 8 schools would represent a collective loss of roughly $3.3 million dollars which is a lot more than just pocket change.

Although at the moment we await a final state budget hopefully city school allocations for the 2023-2024 school year won’t be too far behind. Funding from the state plays a critical role in the school budget. City budget allocation memos for the upcoming school year have historically been released sometime in May or June. Title I is always among the early allocation releases. I encourage interested folks to check the NYC Public Schools allocation memos for this particular memo that contains a treasure trove of useful data not only about the Title I dollars but also adds clues about demographic data on our schools generally.